|

The following treatise is written expressly for young cartoonists starting out and wondering what in the world may fill the vast, empty page before them. Like most cartoonists, I started young, The earliest cartoons I still have copies of, then, date back only to mid-high school, When I got out of school, I worked as an aerospace engineer designing cruise missiles (speaking of nuclear holocausts), but I quickly sought out cartooning work, and ended up moonlighting a little during my year in San Diego. I stayed with engineering for that long, just to prove to myself that I could cut it. Then I took the first boat out of there. It was a copywriter's job at an ad agency in Detroit, the agency that launched another copywriter-turned-cartoonist, Cathy Guisewite. Though I had no advertising portfolio, I got the job on the strength of my cartoons and figured it was my stepping stone to a career in silly pictures. Until advertising sucked me in and I hardly lifted a cartooning pen for nearly a decade. I managed to win a Clio and a bunch of other awards for my efforts. But I wasn't drawing cartoons. I went into advertising as a stepping stone to cartooning, but I wasn't stepping. I was doing plenty of creative stuff in my after-hours, comedy mostly, but the one thing I wanted to do most, I was avoiding. So I took a leap. I quit my 9-to-5 job. The comedy I had been moonlighting in nightclubs gave me something to pay the bills. No, not the comedy itself. Being not quite stand-up and not quite improv, it was, well, to strike a theme, From there, perhaps out of a desire to appear on stage in proper trousers, we moved on to the Waveland Radio Playhouse. We performed original spoofs of old radio adventure genre shows, beginning with "Rip Then came Theatre of the Bizarre, a three-and-a-half year adventure to the very fringes of comedy. It ran weekly in the richly atmospheric rathskellar of the Elbo Room in Chicago. It was an outgrowth of an earlier attempt at the concept, The Serious Art Comedy Show, and launched several careers. My buddy Jim penned a two-minute, throw-away schtick, to serve as filler between acts, which the barmaid suggested he expand into a book. He did. 30 rejections later, he hit number 1 on the NY Times list. Two decidedly outre comics, Matt Walsh and Matt Besser, saw what the other was doing and decided to team up. They went on to found the Comedy Central hit, "Upright Citizens Brigade." I, however, did not become famous through my various bits, not as the tortured torch singer, the inept acrobat, an all-growed-up version of Highlights Magazine's Goofus and Gallant, or the dozen or so other experimental oddities. There were other spin-off shows, such as The Best of Blue Collar Art, in which I played Roy Turdych, workingman poet of the people (i.e., limericist); and I actually took a stab at reading my serious poetry — sonnets, no less! — in a revue or two elsewhere. Bad idea. They're best left to the page. Same with the limericks. Anyway, these various stage adventures let me hone the skills I needed to get actual paying work as a voiceover. Naturally, I specialized in character voices, the more offbeat the better. And performing as many as 70 distinct characters a night with the Waveland Radio Playhouse gave me a fabulous stable of character ideas to spring from. The work was demanding of my schedule, but not of my time. I found long stretches of time between auditions. In that silence, I was once again able to hear my art muses. I started out with a children's book idea, then took to painting seriously. Watercolors, then oils. I was sketching and doing fine art drawings. But I knew that these were all simply to rebuild my cartoon muscles. At first, the only cartooning I was doing was for self-promotional ads for my voiceover work. The ads were wildly popular and were a watershed for the trade magazine that ran them, since a million other actors jumped on the advertising band wagon, thus boosting the rag's ad revenues. Around this time, I made a couple of half-hearted submissions to The New Yorker, but nothing really came of it, mostly because I wasn't really committed to the work yet, and it showed. Meanwhile, my comedy partner Jim was going strong with his books, and I helped him out with writing gags for a couple of calendars that were meant to cash in on the books' success. Writing hundreds of printable gags in a matter of weeks made me think that it was time I came up with that comic strip idea that I always knew would someday come to me. One day soon, it did. I simply woke up with it. I started making sketches, developing characters. Then I stood back and looked at it. It stunk. BUT!... a couple months later, I woke up with ANOTHER comic strip idea. And I mean I literally woke up with it; it all came to me in that crepuscule of semi-consciousness between waking and slumber. This was "Monkeyhouse." In the meantime, however, my style had developed significantly from the daily discipline of drawing (let that be a lesson to you, you aspirants out there: draw every day!). I had begun freelancing as an illustrator, picking up decent work here and there and augmenting my acting income. And it wasn't terribly long after that that I decided to launch another sortie at The New Yorker. Now, this is against every bit of advice anyone has ever given about breaking into the magazine market. Back then, when there were still many other magazines publishing cartoons, the proper thing was to sell to a handful of the others and get good before trying to make it in The New Yorker. It made perfect sense But my reasoning was simple: if I wasn't good enough for The New Yorker, I didn't want anyone else to see my work. Predictably, my first batch was rejected. Then came the shocker. The phone rang. They wanted to buy a cartoon from my second batch. (Secret Tip for beginners: Here's how you break in at The New Yorker. You make copies of your cartoons, stuff them in an envelope, and send them in! Yep, it's that simple. Either you'll sell something or you won't. It depends entirely on the work. Okay, it's not quite that simple. You have to keep sending them, week after week, for as long as it takes.) After the dizziness wore off a few weeks later, I got into the regimen of submitting more stuff regularly, weekly if possible. And they bought another. Then another. Then it became semi-regular, roughly monthly, which is how it stands presently, despite some dips in my submissions or their appreciation here and there. (A major highlight of my cartoon career was being out to lunch with a bunch of New Yorker cartoonists and hearing them discuss a cartoon from the magazine which they didn't get. It wasn't mine, but I did have the rare honor of explaining the gag to them. Man, I felt so sophisticated!) After I had a backlog of a couple hundred cartoons, I started submitting them to other magazines, and they started buying them. It was very heady how quickly my résumé expanded. As my gag cartooning career was blossoming, I had also been sending "Monkeyhouse" around to the other syndicates, one at a time, every few months—sometimes a lot more than a few. When it came back, I'd slap another cover letter on it and stuff it in an envelope. I had racked up maybe three more rejections when my luck changed. Once again, it was a phone call. It had been a good week

In 2009, an idea for a cartoon gag took me in an unexpected direction. Well, half an idea. I couldn't quite make it funny enough to invest the ten minutes it would take to draw up a rough and have it rejected. But as I was letting it die, I saw it from a different angle. And it sparked an idea. Now, I have let lots of great ideas go for lack of resources to pursue them and make my millions, but this one took only a cartoonist and someone with computer skills. I emailed someone I know with the latter. I asked if the idea was "crazy or just a joke." He suggested we talk about it over lunch. Three years later, I was on the stage at a major tech start-up venue in Silicon Valley, and that cartoon-that-never-was was creating a buzz as the next big thing in market research—before it found its real home as a tool to help people with autism and other emotional recognition disorders. So a non-starter of a cartoon led to a now patented animatable graphic index of the full range of emotional expression. And that introduction to the invention process led to me waltzing back into the patent process, in 2014, with an actual physical gizmo I made to hold my glasses and not let them flip open, fall out and get mowed by the lawn mower—which they did when I tried hooking them over my collar like most folks do. That product is working its way to market right now. This is the wonderful thing about creative work: doing one thing can take you on unexpected detours to something else entirely, but only if you remain open to it. Another example of that: Outside of cartooning, I used to sing in my church choir. One day, a handful of choir folk saw a friend perform in a show in a church basement. Someone said, "Hey! We have a church basement..." A sacristan at church was married to a composer I used to know through advertising. A couple guys in the choir had experience in set design and stage managing. And before you could say "Andy Hardy," we were writing a musical. "Saints Alive!" And then another, "Pitchmen." Since then, I knocked out a few more musicals, Despairadise, My Dead Irish Mother, and Fässi Goboggan and the Curly Headed Girl. A couple have had minor stagings. Various distractions and derailments have kept them from being stagebound elsewhere, but they'll keep until I'm ready to get back to them. The important thing is what I learned from those processes. Mainly: it's great being a cartoonist working on your own with total creative freedom, but it's way more exciting to work in collaboration with other creative people. It takes you in the most unexpected directions.

And that's about it, in a very large nutshell. If you've read this far, you are probably an aspiring cartoonist trying to figure out how to break into the business. So I will now answer your lingering questions, the first two I won't even bother to spell out: 1) A Hunt Imperial 101 crow quill nib with FW Acrylic waterproof ink (currently) and a black watercolor wash (yes, you have to use expensive sable brushes, or you will ruin your work) on Strathmore Series 500 two-ply vellum bristol. I also use Rives BFK paper sometimes or some other all cotton printmaking paper, just for fun. And I use plate finish bristol for black line work with no wash, such as comic strips or cartoons for The Wall Street Journal. 2) I draw 10 roughs a week (40 or so weeks a year; more if I can swing it) with marker pens on laser printer paper. Then I scan them and organize them in PDF files for submission to The New Yorker, after which I bundle pairs of those 10-page PDF files into a renamed file to submit to the other cartoon markets (you can learn more about these from The Gag Recap). This makes them easier to track. If you want to be extra clever, you can keyword each individual cartoon for easy searching. But I have thousands of roughs in my back catalog I'd have keyword, and so I have never gotten around to that. I also have alerts programmed into my calendar to remind me what time of the month to submit batches where. 3) What is my favorite cartoon of any that I have ever done? The one that I will do tomorrow. And that's what it means to be a cartoonist! Now get out there and have your own adventure. |

|||

penning my first comic strip, "Orville," in the first grade. It featured the eponymous character and his dog Salty. None of the originals survive to this day, and this is probably a blessing, since, this way, I can remember it being brilliantly witty rather than what it probably was — a bunch of pointless drawings of the characters with their names emblazoned inflatedly above their heads. Somewhere around 3rd grade there was a cartoon about another funny-named kid and his horse, and in junior high I did a whole folder full of gag panels, which got lost when some other kids and I tried vainly to start a neighborhood newspaper. Due to a falling out, I never got my folder back from the guy who was to be our publisher (i. e., whose dad had a copier at work).

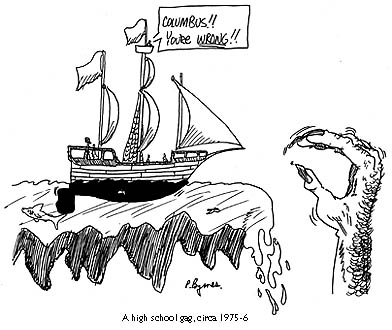

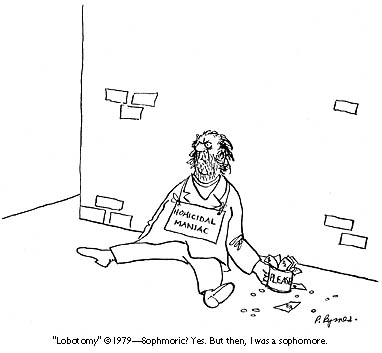

penning my first comic strip, "Orville," in the first grade. It featured the eponymous character and his dog Salty. None of the originals survive to this day, and this is probably a blessing, since, this way, I can remember it being brilliantly witty rather than what it probably was — a bunch of pointless drawings of the characters with their names emblazoned inflatedly above their heads. Somewhere around 3rd grade there was a cartoon about another funny-named kid and his horse, and in junior high I did a whole folder full of gag panels, which got lost when some other kids and I tried vainly to start a neighborhood newspaper. Due to a falling out, I never got my folder back from the guy who was to be our publisher (i. e., whose dad had a copier at work). forty-ish years ago. In my junior year, I saw my first cartoon published. Naturally, it was in our school paper, The Spectrum. I don't think I was consciously planning on being a cartoonist at the time. But, then again, I wasn't thinking of being anything else. When I was picking a college, I visited Notre Dame. It was there, on a tour of the campus, that our guide blithely mentioned that the school had an entirely student-run, daily newspaper, The Observer. My decision was made, right there on the spot, and I could lead you to that very spot if you were bold enough to dare me. I told my parents that it was because I could get to work on a wind tunnel as an undergrad, whereas at Michigan I would have to wait until grad school. My official major was Aerospace Engineering, but, truth be told, I was an undeclared cartooning major. I started out with a strip about campus life, but my then rival and later good friend, Michael Molinelli, was doing a much better job of it. So I did what I do best: something different. It turned out to be a gag panel called "Lobotomy." It was very controversial, and I think not a year passed when a bloc of editors didn't lobby to have me thrown off the paper. Sour grapes, maybe? After all, none of those editors was ever given a full page to do with as they please. About twice a year, I was. One was my Christmas page, the other was usually my "Nuclear Holocaust Page," a collection of grisly themed cartoons. I've grown out of that, thankfully.

forty-ish years ago. In my junior year, I saw my first cartoon published. Naturally, it was in our school paper, The Spectrum. I don't think I was consciously planning on being a cartoonist at the time. But, then again, I wasn't thinking of being anything else. When I was picking a college, I visited Notre Dame. It was there, on a tour of the campus, that our guide blithely mentioned that the school had an entirely student-run, daily newspaper, The Observer. My decision was made, right there on the spot, and I could lead you to that very spot if you were bold enough to dare me. I told my parents that it was because I could get to work on a wind tunnel as an undergrad, whereas at Michigan I would have to wait until grad school. My official major was Aerospace Engineering, but, truth be told, I was an undeclared cartooning major. I started out with a strip about campus life, but my then rival and later good friend, Michael Molinelli, was doing a much better job of it. So I did what I do best: something different. It turned out to be a gag panel called "Lobotomy." It was very controversial, and I think not a year passed when a bloc of editors didn't lobby to have me thrown off the paper. Sour grapes, maybe? After all, none of those editors was ever given a full page to do with as they please. About twice a year, I was. One was my Christmas page, the other was usually my "Nuclear Holocaust Page," a collection of grisly themed cartoons. I've grown out of that, thankfully.

different. A buddy of mine from high school, Jim (these days known as

different. A buddy of mine from high school, Jim (these days known as  Whittingly, Fashion Designer of the Serengheti." We collected glowing reviews from the local press, Chicago Tribune, Reader, and Sun-Times, and we played long runs at the Roxy, the Elbo Room, Boombala and other now-defunct comedy rooms; and we landed a regular feature on WBEZ-FM, the local NPR outlet. Then we branched out into industrial shows, our favorite being at a national convention of casket salesmen, until we retired the act in 1992 after earning literally hundreds of dollars.

Whittingly, Fashion Designer of the Serengheti." We collected glowing reviews from the local press, Chicago Tribune, Reader, and Sun-Times, and we played long runs at the Roxy, the Elbo Room, Boombala and other now-defunct comedy rooms; and we landed a regular feature on WBEZ-FM, the local NPR outlet. Then we branched out into industrial shows, our favorite being at a national convention of casket salesmen, until we retired the act in 1992 after earning literally hundreds of dollars.

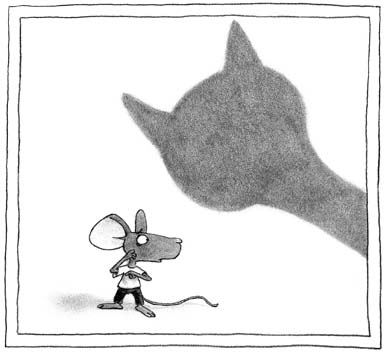

I was one mortgage payment away from broke at the time, so I had to let the idea steep for a spell, while I sold my brain to advertising for a few weeks to restore the coffers. I had bought a house, you see, which is a curse for actors. As soon as you have a mortgage, expect work to dry up. Luckily I had writing skills to fall back on. Within a couple months later, then, feeling flush again, my new comic strip "Monkeyhouse" was ready for submission to the syndicates. First stop, Universal Press Syndicate, from whom "Calvin & Hobbes" had just retired. They liked what I sent and wanted to see more. I whipped up four more weeks in a couple of days and fired it back to them. They pondered, then said it was too eccentric. This stung, because there were two characters I had shoved into the strip that were indeed too eccentric. I had forced them to be that way, and the operative word here is "forced." So I pulled back and rethought the characters before polluting any more waters. The problem characters were the parents, so I killed them. That left the widowed uncle living in the attic as the new guardian. This felt so much better. Universal thought so, too, enough to offer me a six-month development contract. They had some concerns about the cartoon being — can you see it coming? — "different," but their biggest hang-up was with a single uncle raising a 9-year-old girl. They thought "people" would infer bad things. Well, I'm not easily shocked, but this shocked me. It was too perverse even for me to think of it. So I tucked that note into the back of my brain and went on with the development. The uncle grew very naturally into the role of dad, but not in time. They turned down the strip for syndication.

I was one mortgage payment away from broke at the time, so I had to let the idea steep for a spell, while I sold my brain to advertising for a few weeks to restore the coffers. I had bought a house, you see, which is a curse for actors. As soon as you have a mortgage, expect work to dry up. Luckily I had writing skills to fall back on. Within a couple months later, then, feeling flush again, my new comic strip "Monkeyhouse" was ready for submission to the syndicates. First stop, Universal Press Syndicate, from whom "Calvin & Hobbes" had just retired. They liked what I sent and wanted to see more. I whipped up four more weeks in a couple of days and fired it back to them. They pondered, then said it was too eccentric. This stung, because there were two characters I had shoved into the strip that were indeed too eccentric. I had forced them to be that way, and the operative word here is "forced." So I pulled back and rethought the characters before polluting any more waters. The problem characters were the parents, so I killed them. That left the widowed uncle living in the attic as the new guardian. This felt so much better. Universal thought so, too, enough to offer me a six-month development contract. They had some concerns about the cartoon being — can you see it coming? — "different," but their biggest hang-up was with a single uncle raising a 9-year-old girl. They thought "people" would infer bad things. Well, I'm not easily shocked, but this shocked me. It was too perverse even for me to think of it. So I tucked that note into the back of my brain and went on with the development. The uncle grew very naturally into the role of dad, but not in time. They turned down the strip for syndication. They didn't give much reason (to be fair, they weren't obligated to), but alluded to their hang-ups about the "bad things."

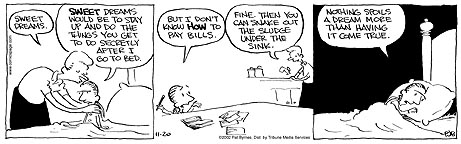

They didn't give much reason (to be fair, they weren't obligated to), but alluded to their hang-ups about the "bad things." already, with calls coming from two or three magazines wanting to buy cartoons, but this call was from the Los Angeles Times Syndicate. They wanted "Monkeyhouse." And they got it. Then, no sooner did they launch their sales effort than they were sold themselves, and they were subsumed by Tribune Media Services. A "transition period" followed, during which I drew my strip for the small handful of papers that bought it in the few minutes before the syndicate sale. I had to spend the first 18 months of the strip essentially without a sales force pushing it. Then when the TMS sales team got it, it was already old news. Awkward timing (or should I say comic?). In any event, it never recovered from its less than blockbuster beginning, and after three years and a game run, it was time for me to pull the plug. On the up side, I got a couple of books out of it—in Portuguese—and proved to the powers that be that I can produce a consistently funny strip day in and day out, even if it wasn't raking in the dough. So the door was wide open for whatever concept I came up with next. Except I never felt like coming up with it.

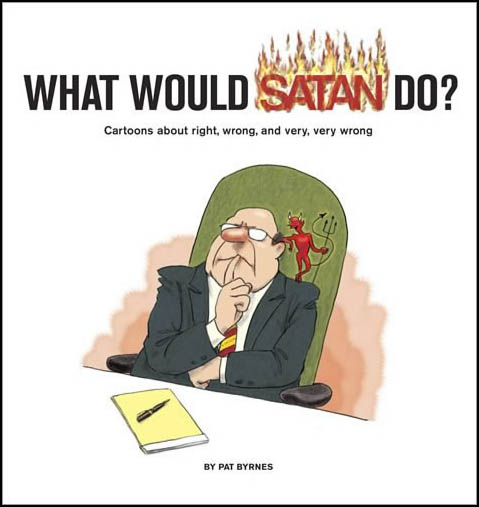

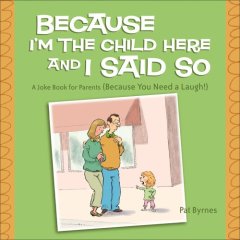

already, with calls coming from two or three magazines wanting to buy cartoons, but this call was from the Los Angeles Times Syndicate. They wanted "Monkeyhouse." And they got it. Then, no sooner did they launch their sales effort than they were sold themselves, and they were subsumed by Tribune Media Services. A "transition period" followed, during which I drew my strip for the small handful of papers that bought it in the few minutes before the syndicate sale. I had to spend the first 18 months of the strip essentially without a sales force pushing it. Then when the TMS sales team got it, it was already old news. Awkward timing (or should I say comic?). In any event, it never recovered from its less than blockbuster beginning, and after three years and a game run, it was time for me to pull the plug. On the up side, I got a couple of books out of it—in Portuguese—and proved to the powers that be that I can produce a consistently funny strip day in and day out, even if it wasn't raking in the dough. So the door was wide open for whatever concept I came up with next. Except I never felt like coming up with it. Since then, I have stuck to magazine gag cartoons. It has led to illustration work for books and advertising, which do a fine job of paying the bills. And I have published a couple of books of my own, and I have more book projects in the chute.

Since then, I have stuck to magazine gag cartoons. It has led to illustration work for books and advertising, which do a fine job of paying the bills. And I have published a couple of books of my own, and I have more book projects in the chute. Speaking of unexpected directions, in early 2001, I was writing gags at my favorite neighborhood sandwich shop. Unexpectedly, I met a girl. Well, a woman. She had a job in local government, which was admittedly kind of interesting but no big deal to an apolitical professional goofball like me. I thought it was more significant that she was smart, pretty—you know the cliché. A couple years later, she became the

Speaking of unexpected directions, in early 2001, I was writing gags at my favorite neighborhood sandwich shop. Unexpectedly, I met a girl. Well, a woman. She had a job in local government, which was admittedly kind of interesting but no big deal to an apolitical professional goofball like me. I thought it was more significant that she was smart, pretty—you know the cliché. A couple years later, she became the